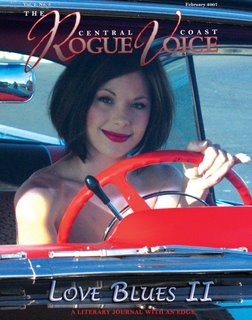

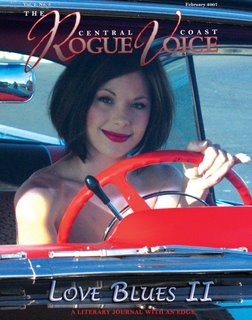

Love II

Being hungry for him made her realize how wonderful sex could be, how two people could do anything with each other and never feel dirty, or guilty.

Being hungry for him made her realize how wonderful sex could be, how two people could do anything with each other and never feel dirty, or guilty.

She was so goddamn crazy angry with Jerry, and the way things had turned out, that she wanted to inflict the worst kind of pain on him.Love

Part IIBy Dell Franklin

When Sally McCormick was attending junior college and still living at home, she’d have these feelings when she woke up in the morning. It was like, well, she was kind of happy, things were going along OK, but something was missing, and deep inside of her there was this feeling something really good, something really terrific and special was going to happen. She could not describe this feeling, or express it to her friends because it was just a feeling that pleasantly tugged at her and promised a certain experience that was going to occur in her life, and it would be the best thing that ever happened to her, and she knew it was going to be love.

Oh, she’d read about love, seen it in movies, and it was in all the beautiful songs and poems, and friends talked about how love happened to you when you least expected it, and when it did happen it was all that mattered, which was not how it was when she’d gone steady with a very nice boy named John Devlin in high school.

When she met Jerry working at Disneyland, it happened instantly. He was this tanned, carefree beach boy type, really handsome, not pretty but manly and charming, with kind eyes, and he was funny, a kidder, and not so serious like John, who wanted to marry her, but looser and natural and there. Though he hung out with surfers, he was more a loner than a follower, and she could see by the way he handled himself at Disneyland during lunch breaks that girls liked him, were interested in him in more ways than one, and some of the girls talked about how sexy he was, kind of a rake, but not a heel or a bastard, and he had this way of looking at her like he knew her secret thoughts and laughed at them, but not in a mean way, but like he saw something special in her, and, of course, it just happened between them like lightning, and at that second it was over for her and all she could think about was Jerry—nothing else mattered.

She went to school, went to work, but all of this was secondary to Jerry. She would have dropped any of those things to be with him, and there wasn’t any doubt they were in love, this was it, they just knew it, and they didn’t want to be around their parents and friends, and they could not get enough of each other, and making love, it was so new, so fresh, so deep, beyond all her previous fantasies, so…complete. She was satisfied, and yet she was not satisfied, as if she was hungry for him all the time, and being hungry for him made her realize how wonderful sex could be, how two people could do anything with each other and never feel dirty, or guilty, because both of them were always giving, trying to make the other feel better, and while they did this they felt their love growing and growing, until it was so full it had to burst, but it didn’t, and she knew then that this was the fulfillment of the feeling she awakened with those mornings, when she knew something like this was going to happen in her life.

***

Since they could not bear being apart, she could not bring herself to think about how lonely and painful it was going to be with Jerry gone for two years in the Army, or bear the burden of him going to Vietnam and getting wounded, or killed! But he reassured her that he would stay alive for her, no matter what it took.

She could not discuss her feelings with her parents. They felt Jerry was nobody going nowhere, a good time Charley, stuck at Disneyland for life. Her friends thought he was a beach boy Romeo with his wavy sun-bleached hair and looks, and he was vain, liking to cruise in his cherried 1955 Chevy and look at the girls. She knew this going in, but it didn’t matter, for she would’ve died to be with him. She did not look at other men. It was like life had not existed before Jerry, and they went on together from here on, sharing everything, and the worst part of his leaving was that she could see things and wish she could share them with Jerry. Every time she drove to the beach she thought of their making love down by the cliffs and caves, and driving around in his car reminded her of their making love in the back seat. They could make love anywhere, because they were always so excited around each other—she could smell his excitement, like a strong scent he gave off, and she loved this scent, and being near him and expecting him to kiss and touch her made everything inside her start churning and she could feel her own scent rising (it was something that happened around Jerry and only Jerry, and it was like being cleansed), and he told her he could smell her scent and it drove him crazy, and when he went down on her it was like he just could not get enough of her, could not stop himself trying to make her feel the most terrible pleasure a woman could feel, and this was what she missed like she’d never missed anything before in her life.

When he left he gave her his car. That’s the way they were. She’d have given him anything she owned if he wanted it, even if it was her most treasured possession, and he gave her his most treasured possession, his cherry ‘55, which he kept immaculate. He didn’t ask her to drive it or take care of it, but gave it to her, and this angered his brothers, who thought they should take care of the car, but he didn’t care, because it was like neither of them had these great big families, but were on their own and away from them and wanted to be on their own private island.

She wrote him every day when he was in basic training, and he wrote her short notes, because he was so busy, and though he said it was very hard, he also said everybody had to go through it, it was your duty, and that her letters kept him hopeful when he thought about being sent to Vietnam. He said that the thought of seeing her again made everything tolerable and rosy, and that every time he got her letter he felt great, and nothing they did to him could dim the happiness that her letters brought to him.

When he finally got a weekend pass she drove up to Fort Ord in Monterey and they never left the motel room, ate takeout and watched TV and made love the whole time, and when he came home for his 15-day leave they were together the whole time, and both parents were angry, but they didn’t care, because as long as they were together nothing mattered because they were together on their own island, didn’t want to get off, didn’t want to let anybody on, and when they wrote each other later on after he transferred to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and finally to his permanent duty station in Germany, they always talked about their island, and how nothing or nobody could ever budge them off it, and when he got out they would stay on that island forever, until they died.

***

His letters from Germany started to change after a while. He had never griped about anything the whole time she had known him. He was always so up, and strong, like a rock, he could not be discouraged and stood up to anything that came along, somebody to lean on, a fortress, her hero. But after a few months at this place called Baumholder, which he called “The Rock,” there started to be, like, a crack in the fortress. He bitched about how terrible the place was, like a prison, but worse, because they had him shooting off these loud cannons and artillery rockets day and night, and the noise never ceased and his ears always rang and he couldn’t hear half the time, and everything was dirty and dusty, or icy and snowing and freezing, always dark and depressing, and he wished he were with her at the beach in the sun, riding the waves and making love, and he didn’t know how he was going to make it for another year, and now her letters were more important to him than ever.

He sounded so lonely, and needy, like a little boy whining for his mother, like, well, dependent on her, while Sally felt that being over in Germany, no matter how terrible, was a situation he should be thankful for, since it wasn’t Vietnam, where guys were getting killed every day, and she told him this, but he wrote and said she could not possibly understand what it was like, and that half the time he wished he were in Vietnam, so he could blow off big guns at the little Charlies from North Vietnam miles away. Now everything he wrote was so down, so negative, and it began to turn her off, and when this happened she felt she was losing what was most important between them, like he was this different person than the one she knew and loved, and she hadn’t seen him in so long, (it would be nine months when the holidays came up) and she was lonely, and it was harder and harder to write the same kind of letters she’d been writing him for a year, and she had to have some kind of life for herself besides writing him, and her girlfriends told her that these relationships never worked, that guys went away in the Army and changed, could not go without women and went to prostitutes and got venereal diseases, and hearing this made her sick to her stomach, when she thought of Jerry with those girls…she just could not picture him being the same way with them as he was with her, but guessed that it was true that men had to have women, especially the sex part, and here she was not thinking about sex, though lots of cute guys who worked at Disneyland were thinking about it when they hit on her, guy after guy, like an avalanche of guys pursuing her, like dogs in heat when Jerry left and one particular guy, a ride operator named Bill Lancaster, who was 26, was relentless in his pursuit of Sally, always telling her how beautiful she was, and he was handsome, and she had to admit she was flattered by the attention and compliments, and she was lonely, and so missed having a man touch her, caress her, hold her, and it was enough to make her cry to think about what she and Jerry had had together and not being able to do it for almost two years…it didn’t seem fair at all, especially if he was having sex with prostitutes and putting his health in danger.

So she went out with Bill. At first they didn’t do anything, just had dinner and drinks. Bill was different from Jerry, more of a hustler, where Jerry, though kind of a hustler, was also more of a man’s man, more of a gentleman than a playboy, and he was romantic. Bill tried to be romantic, but it seemed unreal, artificial, like he had this line, this game he played to set up a romantic atmosphere. But still, he was very convincing, and he kept telling her Jerry was in Germany, and being in the Army meant he was like all the other GIs over there—they drank, brawled, bought whores, became like wild animals, became negative and resented civilians, because it was a time in their lives when the Army turned a man into something different, especially overseas, and it could not be helped, especially if you had the kind of duty Jerry had, and Bill felt it was stupid that Sally deprive herself from the things in life that gave her pleasure and made her feel like a woman, and he said she should never feel guilty, like so many Catholic girls do, and that the Catholic Church and religious parents controlled you and inhibited you from doing all the sexual things that seemed so sinful but were natural, and now Bill was telling her how attitudes and morals had changed in the world, as people were discovering how wonderful sex was, how they were breaking down the old Victorian shackles and living for the moment, and so one night they had a few drinks and went dancing, and started kissing, and for a while it was exactly like she was kissing her Jerry, after they shared her first joint and she was in bed naked with Bill and she wasn’t thinking about Jerry at all, just felt this man’s arms around her and his sex inside of her as he squeezed and kissed and gave her pleasure.

She wanted it, needed it, made up her mind she was going to do all the things with Bill that she’d done with Jerry, wasn’t going to hold back, and after this happened she could no longer bring herself to write Jerry when letter after letter came, asking her what was going on? What was wrong? Did she still love him? Had she forgotten him? Was she in love with another man? Why wasn’t she writing? Then one of his brothers wrote and told him about Bill, and he wrote and asked was she doing the same things with Bill that she’d done with him? And he said he was starting to hate her because she could not be trusted, was like all the rest, a liar and two-timer, and not the person he had loved, because he no longer loved her, and then came the letter of all letters, the most horrible, spiteful, evil letter any man could write any woman, it just staggered her that he could sink so low—the stuff he said about her, calling her the filthiest, lowest, basest whore on earth, garbage, phony, hypocrite, a siren, a pretty little goody-goody Irish puritan who was nothing but a lowdown cocksucking cunt, a depraved monster who belonged in porno movies, a person who disgusted and, revolted him, and that as far as he was concerned she was dead, and in fact he actually wished she was dead!

Sally cried, was never so wounded, so stunned, and when she showed the letter to Bill, he said Jerry had lost it and cracked, was weak, a loser, a psycho, and she was lucky to find out what he was really like, and when she thought how she’d felt about him, and how she’d loved him, and the island they’d been on, she was sick to her stomach, threw up, and went into a depression, and drank, and she was so angry, so goddamn crazy angry with Jerry, and the way things had turned out, that she wanted to inflict the worst kind of pain on him, wanted to hurt and slice him to the emotional core, so his suffer-ing never ended and he realized what a rotten bastard he’d turned out to be, and when she thought about how he had made her feel about him, and how she could discover in herself the rage and viciousness and evil hatred to feel this way about somebody she had once loved so deeply and pledged to love forever and have babies with, it occurred to her that perhaps Jerry was right, and there was this part of her that was just as rotten and sluttish and filthy and no good as Jerry accused her of being, and that she was really not the person she had always thought she was, and so, in a drunken orgy with Bill, to per-manently sever what had been between her and Jerry, she made these ghastly pictures of her and Bill having wild sex together and mailed them off to Jerry, knowing that they would destroy any last vestiges of hope they’d have together.

But what really hurt and lingered and gnawed at her like a worm eating away at a rotten apple and would not go away was that what they’d had together no longer existed, and what they had together was the best thing that had ever happened to her. The loss of that, the trust and belief they had in each other, the intimacy, the hunger, the little island they had created, to protect each other, well, without that, she unraveled spiritually and plunged into an emptiness so complete, so desolate, that she seemed adrift, outside of herself, lost, and this was when she began to go on crying jags and screaming fits and smoked pot and drank herself to sleep night after night, until Bill abruptly left her and she began sleeping with guys at Disneyland, one after another taking advantage of her demise and fucking her like hungry animals. She didn’t care what they did, or what she did, just wished to escape, be wild, and crazy….

She stayed away from old friends and her parents, just worked at her job in the haze of a hangover, and when she looked at herself in the mirror and thought of herself she saw this different person, this stranger, this tramp, this whore, whose worth was only of the flesh, who was no longer worthy of any man save those who wanted to mount and fuck her until they were exhausted and had had their fill and slunk away, most of them spending as little money and doing as little entertaining as possible before getting her high and….

***

She knew Jerry was getting discharged. He had never written back. A couple months before Jerry was to get discharged, Sally was threatened by none other than Bill Lancaster, who ordered her to shape up and get a hold of her life because he was now her supervisor and would have her fired. She made up her mind to quit drinking, smoking pot, taking sleeping pills. She vowed to be strong. Went to church. Talked to her mom. Confessed every tawdry detail to her priest, which was quite an ordeal, but, in a way, cleansed her. She began eating better and sleeping better and ran a mile every day and buried herself at work and in school. Guys kept asking her out, but she didn’t want anything to do with any of them, or any man, period. And, in the mornings, the old longing began stirring in her again, a feeling something special, some-thing new and exciting was in store. She felt like a young, hopeful girl again, instead of a burnt out whore.

One day she went to the car—Jerry’s car—and there he was, lean-ing against the fender, in his usual Hawaiian shirt, OPs and Mexican sandals, but he looked so different! Older. He was 22 when he went in, and she swore he looked close to 30. His hair was darker, and his face was pasty, like he hadn’t been in the sun for years, and his eyes were puffy and red-rimmed, and he had this scar running down his forehead from his scalp to his eyebrow, and his nose was bigger, and crooked; he looked like he’d been through hell, he was this new person….

Still, he was Jerry. Just being near him, things started working inside of her all over again, and she found herself smiling, because he was Jerry, and it didn’t matter how he looked or how much he changed or how pitiful and weak and angry and crazy he’d become, and as she stood before him he took her hand and pressed her fingers against the jagged scars on his forehead and smiled, exposing a chipped-in-half front tooth, and then they were kissing, and holding, and squeezing tight, and it was like nothing bad had ever happened between them, like they were returning to their island, and everything was instantly going to be OK again, and she could smell him, smell his excitement, his scent, the same musky scent he always gave off when he made love to her, and she knew he still loved her, and they went straight up to her apartment and ripped off their clothes and, she was shocked at how his body had changed, because he was so pale, and a beer gut had replaced his tan, washboard stomach. Still, they fell on the bed, rolled around, groaning, kissing, and his kisses were not tender, or passionate, but brutally hard and overpowering, and the next thing he was straddling her and shoving his penis in her mouth, and then he turned her over and entered her from behind and began ramming her without mercy, ramming her harder and harder, hurting her, and she began crying, and he stopped, and her crying turned hysterical, she beat on the bed, sobbing, and Jerry rolled her back over and held her tight and told her how sorry he was, he was just screwed up, and she was the last person he wanted to hurt, he could not bear to hurt her, and he kissed her tenderly on the neck and told her he’d never hurt her again and would love her forever, and he was crying, crying as hard as he’d ever cried in his life, even harder than he had in Germany. §

Dell Franklin is publisher of The Rogue Voice. He can be reached by email at publisher@rogue voice.com.

Part I of this story can be viewed here:

Love I

Read more!

Washing windows across America: Directions from Texans

I’ve found the law enforcement brain unable to sort through the gray concept of my seemingly motiveless existence.

I’ve found the law enforcement brain unable to sort through the gray concept of my seemingly motiveless existence.

Getting directions from Texans, as it turns out, involves more than an exchange of practical information. It requires the sharing of oral histories and the sacrificing a good part of one’s day.

Washing windows across America

It ain’t easy finding your way through the Lone Star state (episode 17)

By Ben Leroux

Each cop has his or her own style. One might utilize the metallic tap of flashlight on glass. Another may simply yell, “HEY, WAKE UP IN THERE!”

But this Ballinger, Texas, cop wakes me thoughtfully, with three light raps of a knuckle. He gives me some time. “Hello in there?” he says.

Eyes closed, I push myself up into a sitting position. There’s no point in opening your eyes when the beam of a high-powered flashlight is zeroed in on them. Slowly, I reach behind for the dashboard where I keep my wallet. I remove my license and push it through the opened window, toward the source of the white light. I yawn.

“Looks like you done this b’fore,” the light beam says to me.

“It’s the car,” I say. “It draws the wrong kind of attention.”

As the light is lowered onto my license I can see that my copper is a thickset ‘ol boy with a golf ball-sized plug of chew in his cheek. He communicates with the station while splattering intermittent streams of chaw onto the Wal-Mart asphalt. A shrieking dog barks off somewhere.

Before his knock, I’d been down the homestretch of one of my best Wal-Mart sleeps yet. This Ballinger Wal-Mart was not your typical Super Wal-Mart with 24 hours of slamming car doors, bawling car alarms, earth-shaking stereo bass, or refrigerated semis grumbling all hours of the night. No, this was a quaint little box of a Wal-Mart, no bigger than a Rite Aid. After closing at midnight, the parking lot had become almost serene, with a perfect mix of fresh air and warmth flowing through the open windows. It had put me out in minutes.

“I didn’t mean to disturb you,” says the cop, handing me back my license. “I’d seen you earlier in the day and I was checkin’ to make sure you was OK.” He drops another deluge onto the asphalt. “SHUT UP, MAYBELLE!”

I start to duck under the covers.

“That’s Maybelle barkin’,” he says. “She don’t shut up. YEW SHUT UP, MAYBELLE! Here we had a murder three weeks ago, and I had to leave the investigation to come and take Maybelle in fer barkin’. She’s a sort of a Spuds McKenzie type. What you doin’ anyhow—just traveling or somethin’?”

I don’t go into much detail with him. I’ve found the law enforcement brain unable to sort through the gray concept of my seemingly motiveless existence. Though they detect no threat from me, the procedure manuals in their minds have some trouble with it. I’ve tired of watching their tortured eyes grapple with such fuzzy data. Out of pity, I now cut it short.

“Okay,” he says, after a silence. “You can go back to sleep now. I just wanted to make sure you was okay. YEW SHUT THE HELL UP, MAYBELLE, OR I’MA COMIN’ OVER THERE T’GITCHYEW!! I apologize for Maybelle. Hope she don’t keep you up.”

***

Of course, there is litte sleeping after a late-night brush with the law, no matter the outcome.

While scarfing down a breakfast sandwich at a nearby Sonic, I remember that I am out of clean rags, so at random I pick a young Sonic employee to ask for directions to a Laundromat. She leads me out to the road.

“Go down’ear,” she says, fishtailing her hand through the air. “You go down’ear issaway, then attaway, then issaway two more times and you’ll see the laundry there.” She does the same motion each time.

“So a left, a right, then two lefts?” I ask.

“You go issaway,” she says. “Got it so far? Then attaway. Then issaway-issaway.”

“But you’re doing the same thing with your hand every time.” I mimic her swerving hand movements.

“Okay, look’ear. I’m gonna tell yew one more time. Now listen. You go issaway….”

“Thanks,” I say. “I’ll find it.” I start to leave but she stops me.

“You should know that only two of the dryers work.”

“Well, which ones?” I ask.

“Ones on iss’ear end.”

“Which end?”

“Iss’ear end.” She fans her hand back and forth in no special direction.

“You mean the end closest to us or the end closest to the front door of the Laundromat?”

“Just the ones on iss’ear end. Ones on atta end don’t work worth diddly.”

I find the Laundromat by doing the opposite of what I think she means.

Getting directions from Texans, as it turns out, involves more than an exchange of practical information. It requires the sharing of oral histories and the sacrificing a good part of one’s day. Even then, directions come out either ambiguously inaccurate (like the ones from the Sonic girl), or drawn out in such a tedious fashion as to reduce a normally patient man like myself to a curt, interrupting asshole that vanishes prematurely, brain numb with rage and boredom.

Waiting for my rags to wash, I sit on the Laundromat sidewalk and replace a rubber squeegee blade. While they dry, I read Checkhov and watch the people of Ballinger go back and forth lazily through town.

I’m the only person at the Ballinger Laundromat in the middle of the day. It’s the kind of moment I feel like the luckiest man in the world–like maybe I’d finally gotten it right. Texans could give me all the bad directions they wanted–have me going in circles the rest of my life, and what would it matter?

Walking downtown Ballinger, my duffel bag is stuffed with clean, warm rags. But downtown isn’t much more than a few streets of old buildings–many of them gutted and crumbling. And not much interest in windows. I am about to suffer a shutout in Ballinger when an art gallery hires me. In Ballinger, an art gallery sells oil paintings of cowboy boots, horses, deer, barbed-wire, and saddles.

As I do the outsides, a man at the candy store next-door comes out and leans against his brick wall and watches me. He’s got a potbelly and a cheap, thin western shirt tucked into faded turquoise Wranglers.

It’s a little past noon when I finish and start packing up. Maybe because of fatigue from the lost sleep, or maybe because I am masochistic, I decide to ask the candy-store man for directions. I’m ready to move onto the next town down the road–Coleman.

I begin by asking him how he’s doing.

“Well…ah’m …oh…” he starts.

It’s a step I could have skipped. In fact, I could have skipped the whole process. How hard could it be to find the gas station in Ballinger?

“Good, good,” I interrupt. “Glad to hear it. Hey, can you tell me where the nearest gas station is?”

“…ah’m doin’…good…I sup-pose… ”

“Great. And where’s the nearest gas station?” I start to feel closed in. I’m thinking about bailing on him.

“Uh?…the whay-er?…to get to whay-er?”

“Gas station, gas station. Gas for my car.”

“Ohhh…you want some…gas?”

“Yes. Yes.”

“For your car?”

He lights a cigarette and tucks a thumb into a belt loop and settles in against the wall.

“Well now,” he says, “…useta be was one down by the old…”

I leave him there talking to himself. I know how the rest goes. Shortly, other citizens will be called over. A committee will assemble—a committee devoted to helping me get to where I want to go. I will be asked to explain why I want to go there, what I plan to do once there, where I am going afterward, where I am from, and why I am traveling without my family. While repeating answers, I will massage my temples and look for an escape route.

I do the opposite of what I think the candy-man means, and find the gas station and the road to Coleman.

***

The next knuckle is taut, and void of the courtesy and politeness of the knuckle back in Ballinger. This knuckle is accompanied by the grating squelch of police radio, and the stink of stale aftershave.

Trying to collect myself, I sit up, dig through a pocket, find my wallet, and stick it out the window.

Waiting behind the wheel, I try to remember where I am. A town called Coleman, right? When I’d gotten into Coleman, I couldn’t keep my eyes open, so I’d pulled into the first patch of shade I’d seen, and that was where I was now–resting in Coleman.

As my eyes close and my jaw tries to drop to my chest, the wallet is shoved back at me.

The wallet is one of those tacky yet practical things with a clear plastic window for your ID on one side, and a money-clip on the other, and that money clip is where I store my life’s savings. This day, it is a couple tens and a few ones.

“You might want to remove the money from this thing before handing it to a police officer. In fact, you might want to remove your license period. Don’t you think that would be a good idea?”

“Oh yeah,” I say, wiping drool from my chin. I take my license out, and hand it to him.

In half-coherent garble, I try to explain to him what I am doing in Coleman. He looks away, his sharp-edged face bothered by my speaking. I start to nod off again.

He finishes talking to the station and hands me back my license.

“Do you know where you are parked sir?”

“Coleman, right? I thought it was Coleman.”

“I want you to look to your right, sir.”

I lean over to the right, and look through the passenger-side window at the tall cinder-brick wall that had been providing me with my shade.

“What am I looking for?” I say to him.

“Look higher.”

I look higher up the wall and see painted in capital letters: FUNERAL HOME PARKING ONLY. I start the Plymouth while apologizing.

“Do you think it’s wise to park next to a funeral home? If I hadn’t a come along, you would have blocked a funeral that is comin’ through here in about ten minutes. Now you go find somewhere else.”

Relieved not to be in custody, I drive around Coleman. Once awake, I park and get out and start looking for work.

It pays off: portrait studio, hair salon, cable TV office, and home-furnishing store.

Taped up on the insides of the windows of Coleman are posters for their annual Fiesta de la Paloma, with its brisket contest, Miss Coleman beauty pageant, line-dancing contest, and Championship Dove Cook-Off. They are juxtaposed with photo placards of hometown soldiers stationed in the Middle East.

I put a coat of soapy water over those young shaven faces, and as I clear the water away with the squeegee, I try to imagine what they looked like as kids going to the Fiesta de la Paloma with their families. I wonder if any have attended their last.

I get about ninety dollars out of Coleman. Next stop, Brownwood.

Packing up, I see a guy coming my way—an intellectual-looking guy wearing a tie and slacks, and carrying a briefcase. Just to dispel my stereotype of Texans as incompetent direction-givers, I stop him. I decide to appeal to his intellect. He looks like a man who knows which way things are.

“Can you tell me which way is south?” I ask him. Brownwood was actually southeast, but if he could get me going south, I could find east.

“Where was it you were wanting to go?” he says.

“South.”

“But where.”

“Just south.” I say. “South is all I need to know.”

“Where south though?” he wants to know.

“Just point me south. I can get it from there.”

“Sir, if you will tell me where you want to go, maybe I can help.”

“Southeast, then okay? Does it matter?”

“Where in the southeast are you trying to get to?”

“Okay, dammit. Brownwood.”

“Oh, Brownwood,” he says, laughing the kind of laugh people laugh when they’re convinced they’re dealing with a moron. “Why not just say that? You follow that road there.” He points to a road.

“So that road goes south then,” I pronounce. I want to win this one. I need it.

“I thought you wanted to go to Brownwood,” he says. “Brownwood’s that way. Hey, you have to know where you want to go. I can’t help you unless you know where you want to go.”

He walks away, shaking his head with disgust. He was a man who had little patience for south or southeast. He just knew where Brownwood was. To him there was little sense in going more than one direction at a time. §

Ben Leroux writes from a motel room in Morro Bay, and still plies his trade as a window washer. He can be reached at ben@roguevoice.com. Read more of his "Washing Windows Across America" series here:

Evicted From Wal-Mart (episode 9)Santa Fe Pride (episode 10)Leaving Las Vegas (episode 11)Tucumcari: End of the mother road (episode 12)Clovis ain't Texas (episode13)Welcome to Muleshoe (episode 14)Dry times in Lubbock (episode 15)Zen and the art of messing with Texas (episode 16)

Go to the main page for this month's Rogue Voice

Read more!

Choosing a path

I peeked through the flap of our tent and saw a figure in the darkness digging through Brian’s backpack.

I peeked through the flap of our tent and saw a figure in the darkness digging through Brian’s backpack.

Tom shifted in his chair, and breathed out a lung full of distress. He might as well have farted.

Choosing a path

Being lost isn’t so badEditor’s note: The following story is part of a series on culture and religion in America.

By Stacey Warde

By Stacey Warde

Magoo’s food began to run out. We handed him treats from our packs and kept him going. He seemed happy despite Scott’s scolding for eating his hat.

“Bad dog!” Scott had said. He would never hit Magoo, only stare and scowl, and Magoo would stare and scowl right back, even licking his chops to prove the point that he’d gotten the last lick.

Scott knew Magoo had a point. You don’t pull a dog’s tail to hitch a ride across the lake.

They quickly made up; Scott petted Magoo’s head and Magoo licked Scott’s hand, then offered a low grumbling growl, as if to say, “Don’t ever do that again!”

The time had come for us to leave the Lower McCabe Lake and begin our trek to Tuolumne Meadows and re-supply. As we descended further into the forest, and closer to mountain campsites, we ran into more people.

“Maybe we’ll meet up with some horny chicks,” Brian said, musing, gazing at the spires of rocks pointing up through the trees above our heads. “Looking for some hard dick.”

Our solitary sojourn beneath the stars had come to an end. Other packers and campers, fleeing their suburban prisons, looking for an escape from their boring lives and jobs, joined us on the path. Students fresh out of school and religious groups in search of God fled into the wild, seeking renewal, searching for the juice that got sucked out of them every day at home and in the work place.

They appeared with smiles, warm greetings, and summer hiking gear, glad to have broken free, no matter how brief, from the dull routine that killed them every day: rising before dawn to battle traffic, pass through the company gate, park the car, find their desk and sleepwalk their way through the day beneath flickering fluorescent lights before returning home to start the degrading cycle all over again.

I’d seen my parents do this for as long as I could remember. They were tired, often broke, but never broken, even when my father stood on the picket line, wondering if he’d ever get his job back. I hated seeing them that way. And I couldn’t imagine spending my life the way they did. After our backpacking trip, I decided, I’d do it differently; I’d make something of my life without the humiliation of sucking up to the boss or taking it up the ass from some corporate schmuck.

“You take what you get,” my father said to me, frustrated that I’d try to look for something that wouldn’t kill me. “It’s just the way things are, son. Beggars can’t be choosy.”

I would have loved nothing more than to prove him wrong. I had tried recently without success to show him that I’d be my own guy. I’d find my own way, like this backpacking trip. When he handed me Army brochures midway through my senior year in high school, I said: “If you think I’m going to join the Army, you’re crazy.”

I had little else going for me. Without Uncle Sam, my future looked bleak. I signed for a three-year stint less than two months after my dad handed me the brochures. I’d go on active duty at the end of summer. In a few months, I’d be grunting through the swamps of Florida, far from the mountains and warm beaches and scantily clad girls of California, learning guerilla warfare tactics and how to stop “the Soviet Threat” from menacing our allies. I was going to be a Ranger and learn how to kick some ass.

My dad was proud. I had made a good choice, becoming a soldier. “You either kill or be killed,” he said, not realizing what he was saying.

***

Backpackers on the trail seemed dazzled by the sun and wind and fresh air—just as we were. I wondered why they would ever go back home. Ten days out of the year. They lived for this moment, I realized. The only ten days that meant anything to them. They’d go home and have stories to tell, pictures to show. They stopped to say hello and chatted up the path they had traveled so far.

“We saw a few elk by the river on the way up,” one said as he tipped his hat and ventured on with his companion.

“Elk. That means bear,” Tom said, looking up from his map, his brow scrunched and the lines on his forehead showing confusion. He put his head back down and studied the map.

Leaving the stark, naked wilderness of the alpine meadow for the lushness of trees and streams and ponds and lakes and mosquitoes, we decided to let Tom navigate. He’d taken the map from Scott after we huddled around its edges to go over our route. The next leg would take us into Tuolumne Meadows. We gave ourselves a day or two to make it but decided to push ourselves hard the first day out.

“Where the hell’s that ridgeline we were following?” Tom mumbled to himself.

“It’s just on the other side of those trees,” I said, pointing. “Look, you can kind of see the spires of the ridgeline if you stand on your toes.”

Tom lifted himself on the tips of his boots, held his hand over his eyes and scanned the tops of the trees. “I don’t see anything.”

“The ridgeline’s over there,” Brian interrupted, pointing behind us.

“No it’s not,” Tom barked. “That’s a different ridgeline.”

“I’m pretty sure it’s the right one,” Brian shot back, still pointing behind us. “I was wondering why you started to go this way. We need to go back and follow that other ridgeline.”

“You’re crazy,” Tom said as he put the map down and we gathered around to consult and find our bearings.

We walked in circles for more than an hour, unable to find a landmark to orient ourselves. We got off trail and beat the brush. The map changed hands several times and we each had a try at getting back on track. We were lost.

“We’d better find a place to set up camp,” Tom said. “It’s getting late. It’ll be dark soon.”

“Good idea.”

We found a brackish pond, the only decent water source in the area. Mosquitoes buzzed in our ears, the air felt thick and heavy, and we were hungry.

“I’ll start some water,” Brian said, “and make us some tea. Then, we’ll eat.”

No one complained about being lost. The worst part was the murky pond and the mosquitoes and the lack of foot traffic and girls. It was supposed to be our night of hooking up, and making camp with some willing honeys we’d meet on the trail. We might even take them into Tuolumne Meadows and into the final leg of our trip. We were so far off the trail we hadn’t seen anyone in hours.

“This isn’t so bad,” Tom said as he leaned against his pack and sipped his tea. “We’ll figure it out; first thing in the morning we’ll find our way back.”

Scott opened his pocket Bible and began reading: “How think ye? If a man have an hundred sheep, and one of them be gone astray, doth he not leave the ninety and nine, and goeth into the mountains, and seeketh that which is gone astray? And if so be that he find it, verily I say unto you, he rejoiceth more of that sheep, than of the ninety and nine which went not astray.”

“It really isn’t so bad being lost is it?” Tom said, sipping his tea, smiling.

***

We found our way back to the trail in the first light. We were determined to re-supply, stuff Magoo’s orange pack with more dog food, and make a quick return to the wilderness.

We got to Tuolumne Meadows before noon, thrilled at the sight of the river, the lush meadows and the general store. The two-lane Tioga Road separated the meadows from the store and the adjacent campground.

We placed our things at an empty campsite and visited the store. I walked alone to the meadow across the way. As I lay upon the tufted grasses beside Tuolumne River, the sun felt soothing, its warm rays calmed me and soon I was out, dreamily lost in the golden green lush of nature.

I awakened to learn that our trip had taken a sour turn. We would have to go home sooner than planned. A park ranger met Scott at our campsite and told him we couldn’t go back into the wilderness with Magoo. We couldn’t stay in the campground, either. No pets. We’d have to leave as soon as possible. We’d have to get a ride out. It put a damper on our spirits.

We called Scott’s brother from the general store and asked if he’d come get us. He couldn’t make it until the next day.

“But the rangers told us we have to leave. We can’t stay here,” Scott pleaded over the phone.

“I can’t do it, Scott,” we heard his brother’s response crackling through the receiver. “I’ll pick you up tomorrow.”

“Fuck!” Scott hung up the phone and scowled at Magoo. “Goddammit! Let’s go talk to the rangers,” he suggested. “If they want us outta here, they’ll have to help us.” We grabbed our gear, ready for action, eager to get on our way. Maybe we could get back into the wilderness, after dropping off Magoo. We’d still have a couple of days.

No, the rangers said, they weren’t available to drive us out of the park and help us get back on the road to June Lake, less than an hour’s drive away.

“Well, how the hell are we supposed to leave?” Tom asked. The ranger lifted his chin, registering the first rise in temper, sizing up Tom, who had proven through his wrestling prowess that he was the strongest of our group, and probably the strongest of any budding man his size and age.

At 17, Tom had already stood down a couple of Marines who threatened to beat his ass in the parking lot of a Carrow’s Restaurant.

“Go ahead, motherfuckers,” Tom had said, facing them, relaxed, ready to roll. Tom was lightning fast and one of the strongest grapplers I’d ever encountered. He could easily lift you off the ground, spin you and throw you hard, and try to break you, and he enjoyed doing it.

I’d stood by his side with two other high school wrestlers and with our best badass glares locked horns in a stare-off with the Marines. They laughed at us, waved us away, and said, “Ah, you’re not worth it,” and went off into the night.

The ranger stood firm, listening, thinking. “Tell you what. I’ll let you guys camp the night here, but then you’ve gotta be outta here by tomorrow.”

“Deal!” Scott said, and we trudged off to find a campsite in the waning light.

We were feeling ragged from the previous long day of pushing hard to re-supply Magoo with food.

“This sucks,” said Brian, as we left the ranger station and found our empty site. We placed our packs on the ground, quickly set up our tents and started dinner.

The campsites offered picnic tables, the first we’d seen in nearly a week. We threw our cookware and a light on the table and made a big batch of macaroni and cheese. We sat at the table and ate; glad to have food, but disappointed that we were no longer in the backcountry.

“I guess we’ll be going home tomorrow,” Scott mused, scooping up his grub.

“We could just sneak back into the wilderness, get up before the sun rises and make a trail,” Tom suggested.

“Fuckin’ A right!” Brian said, hitting Tom on the shoulder. “Let’s do it!”

“Sounds good, but I don’t wanna risk losing Magoo,” Scott said. “The ranger said he’d impound him if he caught us out there. And my father would fucking kill me.” We were more or less stuck, deflated and out of gas.

We drank from a skin Brian filled with whiskey he’d purchased from the general store. The guy behind the counter winked us through the line. He knew we weren’t 21, even though we pretended to be with our beards and rough appearance.

“Let’s drink and hit the sack early,” Brian said as he took a swig and handed the bag to Tom.

“Good idea,” Tom said, “time to get royally fucked up and pass out. Here’s to our last night in the wild.” He hoisted the bag and we passed it around until it was dry.

We left everything out on the table, too tired and drunk, too angry to care about cleaning up or worrying about critters.

I passed out in the tent with Tom. Scott and Brian snored away in their tent at the other side of the campsite. I awakened in the middle of the night to rustling sounds outside Scott’s tent.

I peeked through the flap and saw a figure in the darkness digging through Brian’s backpack.

“Brian!” I whispered loudly. “Brian! What are you doing? Brian, is that you?”

“Gro-o-o-nk. Gro-o-o-nk. Gro-o-o-nk.” The response sounded like an enormous beast chewing grits.

“Tom,” I said, shaking him awake, “Tom, I think there’s a bear outside.”

“A bear? Shit! Duck into your bag!” he said, pulling his sleeping bag over his head.

“What the fuck are you doing, Tom? I thought you were going to jump up and pound some rocks if we saw a bear.”

“Get in your bag!” he said. “If he comes over here and swats you around, you’re not going to like it. If he sniffs at you, don’t fuckin’ move!”

I ducked in to my bag, poking my head out, peeping through the flap of our tent, keeping an eye on the bear. I quaked, fearing the worst, wishing we had never come to this place, wishing we hadn’t been so stupid to leave our food out on the table, wishing the park rangers and wild animals would leave us the fuck alone. Magoo started barking. I started praying.

“Magoo, shut up!” Scott said from inside his tent.

“Scott, there’s a bear digging through Brian’s pack,” I shouted.

“What?”

“A bear!” I said.

“A BEAR?” a startled voice asked from the campsite next to ours.

The beast tore through everything in Brian’s pack and ate all his food. It ripped his backpack into shreds, bending the frame and leaving strips of canvass where the pack used to be. It sampled all of our packs, bending and tearing through them, chewing through granola and nuts and dried fruit, and spitting them out inside our destroyed packs. It swatted at the pots and pans on the picnic table, bending and crushing them, and then, after more than an hour of eating and sampling all our food, it lumbered off into the woods.

***

The next day, we sat on the side of Tioga Road next to the general store, looking like a band of homeless wanderers, disheveled, hung over, our packs shredded and misshapen. Brian bought another fifth of whiskey and we drank beside the road from the skin while we waited for Scott’s brother to pick us up. The rangers left us alone.

His brother arrived in a big pickup truck several hours after Scott called. He pulled up alongside the road and we stood and wobbled and heaved our packs into the back. “You guys look like shit,” Scott’s brother said. “Dad’s pretty pissed off, Scott. He’s waiting for you at the cabin.”

Tom and I sat in the back with Magoo while Brian and Scott jumped into the cab with his brother.

“Fuck, I’d hate to be Scott right now,” I said to Tom. “His dad’s an asshole.”

“I can’t wait for this shit,” he responded. We sat quietly, looking into the vast beauty of the mountains, the distant waterways and lakes, the green forests, and rocks tumbling into the road where goats jumped higher and away from curious motorists. The air felt clean as we rolled up the highway through the pass and wound our way back toward June Mountain. I could feel our brief taste of freedom coming to an end. The closer we got to June Mountain, the more I could feel the claws of parents and obligations and self-righteous assholes clutching my throat.

***

Scott’s dad sat stiffly in an armchair, holding a Bible in his lap, when we entered the cabin. He regarded Tom and me with disdain and turned to Scott, “You boys get yourselves cleaned up, shaven and dressed, and then we’ll talk.”

“I’m not shaving,” I said, brushing past his glare, avoiding the flare of his nostrils, remembering our first free and dissipated nights in the cabin, smoking pot and drinking, before starting our adventure into the Sierra wilderness.

As I stepped into the bathroom, the old man roared, “You’ll shave or you’ll find your own way home!” Magoo skulked down the hallway—head low, tail tucked—into a distant bedroom. That was the last time I ever saw Magoo.

The old man sat patiently as we showered and shaved and put on clean clothes.

He wore reading glasses and pored over a page in his Bible, preparing his scold.

He asked us to sit comfortably and when we had settled ourselves, he peered over his glasses and looked at each of us, as if taking measure and making mental notes.

“You boys are pretty full of yourselves,” he started, directing his gaze at Tom and me, “coming here with your weed and smoking pot and drinking—in MY cabin!”

“Excuse me, Mr.…” Tom started.

“I’m not finished,” Scott’s dad snapped. Still keeping his gaze on Tom and me, he continued: “I have a good mind to haul your butts down to the sheriff’s and let him deal with you.”

“Mr.…” Tom tried again.

“I’M NOT FINISHED! You’ll get your chance to explain yourself in a minute. For now, you listen to me!”

He aimed his gaze at Scott. “I don’t have to tell you Scott how disappointed I am. You already know. Your mother couldn’t even talk about it. Your friends here,” he turned back to Tom and me, “need to understand something.”

“This is bullshit,” Tom muttered.

“You’ve got a rude awakening coming, young man!” Scott’s dad howled, his face turned red and his nostrils flared again. “I’ve already talked to your parents and they’ve got a thing or two waiting for you when you get home.”

I squelched a laugh. Tom’s parents were the coolest people on earth. I could picture them snickering on the phone as Scott’s dad told them how their son had started down the wrong path, and how he was a bad influence and now was the time to steer him in the right direction. I sneaked a peek at Tom and gave him a quick “what-a-fucking-joke” signal with my eyes.

Scott’s dad turned his attention to the Bible in his hand.

“The Bible, as you know, is the word of God. Its words bring comfort to your troubles and afflictions. Its guiding light will either chasten or comfort you, depending on where you stand with God.”

Tom shifted in his chair, and breathed out a lung full of distress. He might as well have farted. Scott’s dad flashed his eyes at Tom and continued.

“Solomon was the wisest man who ever lived,” he said solemnly, “and he wrote a book of Proverbs for young men like your selves, who need guidance and instruction. Listen to these words, gentlemen, because they could mean the difference between a life of misery and a life of joy.” §

Parts I and II of this trilogy can be viewed here:

Hat's in the wind (Part I)Magoo eats it (Part II)

Stacey Warde is editor of The Rogue Voice. He can be reached a swarde@roguevoice.com.

Read more!

Rogue of the month: Lori Lynn Melton

YES THEY’RE REAL Lori Lynn Melton isn’t shy about her guns and wants you to know that not only are they real, “THEY’RE SPECTACULAR."

YES THEY’RE REAL Lori Lynn Melton isn’t shy about her guns and wants you to know that not only are they real, “THEY’RE SPECTACULAR."

(Photo by Stacey Warde)‘Only on occasion do I get out of hand. I’ll do my shots of Yukon Jack, or my favorite—Kahlua, Bailey’s, and a floater of 160 proof Stroh’s.’

ROGUE OF THE MONTH

The ex-Amazon bitch from hell

One of the last of the genuine saloon girls

By Dell Franklin

Back in the day, when Happy Jack’s Saloon in Morro Bay (since 1927) was one of the wildest fisherman’s bars from Alaska to San Diego, Lori Lynn Melton, in all her glory, and known as the self-pro-claimed “Amazon Bitch From hell,” was the day bartender.

I’m now hanging out in the same bar, only it’s called the Fuel Dock, and the sewer stanch and shark-infested grotto-like environment has been replaced by a cleaner, brighter, stylized atmosphere. And Lori Lynn still holds down the day shifts.

“You have a bunch of brothers, right, Lori Lynn?”

“Yep. They range from seven feet two to the runt, six feet eight.”

“So you know men.”

“I know men. On a personal basis, these days, I prefer dogs. I just lost my Lab, Lilly, so I’m down to three cats, and it’s not enough. I’m about ready to get a new dog to greet me when I get home from work.”

“You like animals more than humans?”

“Most of the time.”

Back in the day, Lori Lynn’s running mate and compatriot was a voluptuous and volatile blonde who went by the self-proclaimed moniker of “The Sidewinder.” Together, they went bar-hopping in tight T-shirts, tight Wranglers, big belt buckles, and cowboy hats.

“What bars did you hit?”

“All the local taverns in the county that had action and live music. If there was no action, we made it.”

“How were you welcomed?”

“People looked up and saw us and said, ‘Trouble just came in the door.’ We never entered a bar without our calling card—the primal scream. Mine’s the loudest, longest in the county, and it climbs in octaves to this piercing sound that causes some people to fall off their bar stools.”

“Uh-huh. So, did you intimidate men?”

“Yep. Still do.”

“But at this point you’re the ex-Amazon Bitch from Hell, right?”

“Right. I wore my voice out. No more primal screams. Less boozing. Only on occasion do I get out of hand. I’ll do my shots of Yukon Jack, or my favorite—Kahlua, Bailey’s, and a floater of 160 proof Stroh’s.”

Back in the day, Lori Lynn worked at Happy’s with the legendary “Jackie,” a strapping knockout of an Amazon blonde herself—ex-stripper and biker chick from Orange County who took the bar community by storm, causing some cringing among the matrons of morality plaguing Morro Bay at the time. Just being around Jackie was scandalous.

“What about Jackie?”

“She’d ride in on the back of a motorcycle, right through the bar, get off, go to work. She could dance. She could flirt. She could cuss and chew ass and cry with the best of them. Sometimes, when the place was packed, and she’d had a few mudslides or shots of Jack, she felt it her duty to liven things up, so she filled up this squirt gun that was a dead ringer for an erect penis with balls and hit the dance floor, waving it around, squirting everybody, flushing out slummers and those who couldn’t take Happy’s.”

“You didn’t do that sort of thing, did you?”

“Of course not.” Looking coy.

“What did Jackie teach you?”

“Tits for tips. I got ‘em, make sure you show ‘em just right.”

“They still look good, kid.”

“You got it,”

“What size, if I may please inquire?”

“No problem. 38 D cup. And they’re real.”

Back in the day, when fishermen, still in boots and stinking of fish and sweat, trekked up to the bar from the embarcadero with wads of big bills after a good haul on the high seas, Lori Lynn faced them with a smile and the goods. Good with the bottles. Kept a neat bar and a pleasant, comfortable rap. Had a following.

“So what was it like when fishing was going strong?”

“Well, a lot of the people who come in now probably would not have come in then. There was more trouble and stress, more danger, lots of fights and craziness. Guys pulled knives and guns. Drugs and sex in the restrooms. Sometimes you mopped up blood. There used to be a big group of guys who fished who called themselves the “Brew Crew.” They were like cowboys coming in off a cattle drive. They kinda treed the bar, throwing things around, scaring people. Every time you turned around they were waving empty beer bottles or glasses or money at you. Guys came all the way from the coast of Oregon and Washington for action in this bar. I tried to corral them, but not always.”

“What are they doing now?”

“Not fishing, with the exception of one or two. Married. Kids. Real quiet. Some died at sea, and some are probably in jail.”

“And those days are over?”

“Over. Fishing’s just about gone in this town. I miss those guys. They were real characters, with big hearts under those rough edges. Now it’s more of a Yuppie crowd, and business is way better, and working here is really stress free and fun.”

Back in the day, there were very few female bartenders around town. Those that were had the wherewithal and attitude that allowed them to deal with the worst elements. A few of them worked at Happy Jack’s. Many of them suffered and paid dearly for it. They’re long gone. Lori Lynn remains. Fifteen years at the same bar. From Amazon Bitch From Hell, she morphed into an old pro, last of the genuine saloon girls left in the area, or perhaps the county.

“Young girls are hired right and left all over the county to tend bar these days, Lori. I’m talking twenty one, twenty two, and hot, hot, hot.”

“Yeah. I was thirty when I started, and hot. Had some seasoning and savvy, too.”

“What do you have that these young’uns with the big guns don’t have, now that you’re a middle-aged woman?”

“I still got my guns. And I know how to handle

trouble, not make it, not be it. I can anticipate trouble right off, and diffuse it.”

“You no longer work nights, right?”

“Not even. At night, the monsters, the tweakers, the Frankensteins come out. I got my calm little day crowd, my Happy Hour crowd. I’ve got people from age 21 to 94. We have fun without hurting each other. It’s just right.”

“But there's no more dogs in the bar.”

“No. The county doesn’t allow dogs in bars. Too bad. Back in the day, dogs were player friendly. The roughest, toughest, most violent fishermen had dogs that were so mellow—opposite of their masters. We wanted those dogs in the bar, because they worked as a great tranquil-izer….”

“And they got guys laid.”

“Yep.”

“Well, Lori, we’re just about done. One more question: Are you as tough as you made yourself out to be, back in the day?”

She juts out her hip and thrusts out her chest and challenges me with a sassy look. “What do you think?”

“I think some women are fawningly sweet and cutesy-cutesy and goody-goody, but sometimes, inside they’re like poisoned Hostess Twinkies, cold as ice, calculating as the women who marry an asshole like Donald Trump. I think you, beneath the salty surface, are a creampuff, and a very vulnerable one at that.”

“All right. That’s enough. Interview over.” §

Meet some of our previously featured "rogues" here:

Mandy DavisCasimir PulaskiJim RuddellSteve Tross

Go to the main page for this month's Rogue Voice

Dell Franklin is publisher of The Rogue Voice. He can be reached by email at publisher@roguevoice.com.

Read more!

Life in the cage: Sleepless in Soledad

The wife left me once she found out my sentence was 25 years-to-life. My handful of female friends slowly reduced to zero as time passed. They moved on with their lives; got married, had kids.

The wife left me once she found out my sentence was 25 years-to-life. My handful of female friends slowly reduced to zero as time passed. They moved on with their lives; got married, had kids.

At the Mens Colony, I listened religiously to 91.3 KCPR FM, the local college radio station broadcast from Cal Poly, to feel like I was not housed in prison, but at a college university dorm.

Life in the cage

Sleepless in Soledad

By David Valdez

As long as I can remember, I’ve always hated soap operas. My mom was hooked to the classics: General Hospital, One Life to Live, Days of Our Lives. Each episode a mix of real life stories mixed with fantasy, drama, adventure, suspense and romance.

I dreaded when it was my girlfriend’s turn to treat. Dinner and wine was always fine, but in order to sixty-nine I’d have to endure two very long hours either at the movie theater or on the living room couch watching her choice of chick flick.

Went through the motions; holding her hand, letting her cry on my shoulder, holding her during certain scenes, shedding a tear now and then to show solidarity. It was a means to an end. If I wanted to get some, I had to show her that I really believed such tales of love and storybook endings really can happen in our daily lives.

One evening we went to the local movie theater with my mom to see “Sleepless in Seattle” with Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan. As a radio personality in Los Angeles, I related to this love story about a female disc jockey who meets her prince charming, an avid listener of her radio show.

Doing Top 40 radio three years, I talked to women listeners every evening. Developed a fan-base of regulars that jocks call “groupies.” They called in daily just to talk about anything. Between playing songs on the play list, I was a therapist on the phone request lines.

Women often offered to come by the studio, to do any thing I wanted for concert tickets, or just to hang out. If a caller sounded like a beauty, it didn’t always turn out that way. To screen the ladies, I’d tell them to meet me at a live remote broadcast, which could be at a nightclub, bowling alley or sports event. If she turned out to be a whale, I’d do my best to hide behind the station promotional van. If she was a babe, well, you know what happened.

Throughout my experiences, I realized the power of celebrity. We all fall in love with actors, porn stars, models, sports figures—even radio personalities. We wish we had what they have, or the life they live. We are sucked into their world as an escape from our own reality. Hollywood and the movie and music industries exist, and continue to thrive, because of their fans.

If there were no sizzle or hype, we wouldn’t give a rat’s ass about Brad and Angelina or Tom and Katie.

During the last decade of doing time, with only a television set and radio to experience, see and hear what is going on in the outside world, I found hope in certain radio personalities, always looking forward to their next show. Particularly, three female jocks I developed interactions with while serving my time in prison.

***

Alison

While housed at Tehachapi Prison, a maximum-security Level IV prison located in the Tehachapi Mountains in the middle of nowhere, not one woman visited me. The wife left me once she found out my sentence was 25 years-to-life. My handful of female friends slowly reduced to zero as time passed. They moved on with their lives; got married, had kids.

My once hopeful soul succumbed to loneliness. At my lowest point, feeling depressed, taking psychotropic medications just to cope, I began to place pen pal ads on websites, but seemed to get the regular responses from the usual suspects: desperate housewives who wanted to talk dirty in letters since their husbands were impotent and couldn’t satisfy them, gay men who wanted a boy toy to fantasize about. Life felt hopeless.

In 1998, I got transferred to medium security, the California Mens Colony East in San Luis Obispo. CMC was like Disneyland compared to the harder joints. Had a key to my own cell, night-yard until 9:30 p.m. A mini-canteen to buy sodas or ice cream, open all day every day. No prison politics, and lots of television and radio stations.

I tuned in to 91.3 KCPR FM, the local college radio station broadcast from Cal Poly. Listened with great interest to the many youthful female personalities. Young voices who sounded like the hotties I used to date while partying in Orange County or San Fernando Valley. Valley girls. I listened to the station religiously to feel like I was not housed in prison, but at a college university dorm.

One Monday evening, I came across a show called “Blue Monday.” The host, Allison, had a strong, confident voice, as if she took life seriously, yet had a witty side to her, was playful when it mattered. She played two full hours of ‘80s new wave flashbacks from bands like The Clash, Depeche Mode, The Cure, The Smiths, and New Order. This was the music I grew up with in high school. Each song took me back to better days as a free man: the frat parties, one-night stands, special songs that reminded me of girlfriends from my life on the outside.

Since she took requests from listeners, I decided to write her a request. Didn’t think she would even acknowledge my request. After all, I’m a prisoner perceived as a piece of shit who has nothing coming. Even newspaper reporters will tell you that prisoners have no credibility. It would be fair to say that any woman who gets a letter from a stranger in prison would think the guy is a stalker.

I listened to the next show with great interest to see if she would play my request. From 7 p.m. until 9 p.m. I had my own portable radio perched on a shelf, anxious to see if she was as special as her personality on the air, if she could look past judging me and view me as a human being.

She didn’t brush me off. In fact, she played my request, starting off her show by saying, “This is for you, Dave, at CMC. Here’s The Cure with ‘Just Like Heaven.’”

The song took me back to my adolescent days when I just got my license to drive. My first car, a low-rider VW Bug. Weekends cruising on Balboa Avenue in Newport Beach. Bonfire parties on the sandy coast of Huntington Beach. Friday nights dancing with hot babes at Studio K in Knott’s Berry Farm. Saturday nights at Videopolis in Disneyland. Paying off the wino old man, a fixture on the sidewalk in front of the liquor store, to score us some beer. Strawberry Hill for the ladies. Coming home with a pocketful of phone numbers from all the chicks I scammed on.

Alison gave me an inch. As a desperate lonely man who felt accepted for the first time in years, I proceeded to see how far I could go with her. I began to write to the station every week and ask for hard-to-find songs, challenging her. She always came through, even finding a rare late ‘70s rockabilly cut, “Antmusic” by Adam Ant. She always talked to me, gave me shout outs. It felt as if I knew her. She was all I had.

I pushed further. In my letters, I asked her personal questions about her life, her likes and dislikes, her goals and ambitions. She always addressed my questions as part of her show, in a way that only she and I knew, through innuendo.

It surprised me how attracted I felt to her, and maybe even her to me. When my letters didn’t arrive to her on time (due to some flunky intern at the station forgetting to give her the mail), she sounded disappointed. It was as if my letters uplifted her spirits as well, offering her something fresh for her routine.

After many months, I asked her to write me directly. She never did. I was so curious to see what she looked like so I asked her for a photo. She never sent one. For whatever reasons, she never crossed the line between fantasy and reality. Despite my eagerness to know more about her, she never abandoned me. Alison and I had a connection far beyond just a radio personality playing requests.

I fell into the fantasy, falling in love with her. My emotional stability was dependent on hearing her voice. Sometimes I could feel her pain when she was having a bad day. She could feel my pain too, through the words I expressed in my weekly letters.

Alone in my cell, I cried myself to sleep many nights when she played classic slow jam cuts like Berlin’s “Take my Breath Away,” and Depeche Mode’s “Somebody.”

I fantasized that she would one day write to me, perhaps visit me, save me from a worthless fate, rescue me from the dull life I lived daily. She was Meg Ryan, a radio personality; I was Tom Hanks, looking to her for guidance.

For two years, even with all the publicity of the murders of Aundria Crawford and Rachel Newhouse by CMC parolee inmate Rex Allen Krebs, she kept up the interaction with me on the radio, never judging me a criminal. She gave me hope, always something to look forward to.

It all came to an end when she graduated. I still remember her last show when she said goodbye—one of the saddest and loneliest days of my life.

***

Shaylene

One evening while channel surfing on my portable radio, I tuned in to an alternative rock station, SLY 96 FM, after midnight. I immediately connected with the overnight jock named Shaylene. She sounded like a Cal Poly chick, but she had the “it” factor, that special something a record producer spots in a fresh talent. She had what it took to be a star, just needed a little guidance. So I wrote her.

She wrote back! Began to interact with me on the air. We started a dialogue. When I challenged her, she challenged me back. She even sent me photos. Indeed turned out to be a hottie: 21 years old, athletic, light skin, brown hair, brown eyes, and a local waitress.

She listened to my advice, was improving and developing a style of her own. I saw her potential. Whereas Alison got me through the misery of prison life once a week, Shaylene was with me every evening, five nights a week. I stayed up till 2 a.m. each day, sacrificing my precious sleep, just for the high of feeling wanted, loved, accepted. All I could think about was what it would be like to meet her in person—face to face. Was it possible that this hottie could step foot into state prison, to give me something real, the ability to smell her, feel her, kiss her? I felt love.

Then one evening, she wasn’t on the air anymore. A week went by, and nothing….

She wrote me to say that her program director had intercepted a letter she wrote to me. Apparently, it was returned to sender due to insufficient postage. In the letter she talked shit about her boss, a controlling prick who always told her to follow the “liners,” to follow the play list instead of playing songs she wanted to play. He read the entire letter and fired her.

Despite the unfortunate circumstance, I felt I made a positive difference in her life. She was immediately hired by WILD 106 FM, a Top 40 radio station, doing mid-days. She became a success, even moving to the morning show.

I wonder where she is today….

***

Cheri

For years, I’ve listened to female radio personalities, but none matched the interest I had for Alison or Shaylene. Until last year.

I got transferred from medium to minimum security in Soledad, a rural farming community in the Salinas Valley off Highway 101. I was pleased to find out the prison has satellite cable too! I attached a wire from my radio to the cable system and could get stations as far away as San Francisco.

I came across an alternative rock station in Monterey. I immediately became attracted to the female weekend personality. She sounds young and ditsy, with a strong, confident, yet sometimes childlike voice. She impersonates voices and has a laugh that echoes in my soul.

Every Friday evening, she kicks off her weekend shift with a special ska/punk rock show, playing classics like Suicidal Tendencies “Institutionalized” or current hits from the Aquabats “Idiot Box.” After a month of listening to her, I took the incentive to write her with requests.

I listened attentively for my requests to be played but didn’t hear anything. Two weekends went by, nothing. On the third week, I received an email (delivered to me on paper; inmates don’t have direct access to the web) from the program director of the station.

The letter read: “Please do not write Cheri any future letters to the station. Thank you in advance.”

I wasn’t angry. It’s understandable that any corporate-owned radio station would frown on receiving fan mail from prison. The envelopes are clearly stamped in huge black ink: “Sent from State Prison.” It’s a dead giveaway. However, without a way to call toll-free on the request lines (our phones only dial collect), I was faced with a predicament. How could I let her know I exist, that I long to hear her every weekend and that I want to make requests to her?

One evening, she gave out her personal email address and her MY SPACE address as a way to connect with her listeners. I found a pen and immediately scribbled it down on paper. I then mailed it out to a friend, asking her to print me out the website and send her the personal email message quickly.

Surprisingly, she responded on-air, playing my requests that weekend. I was thrilled! She was receptive to me, even though I was a state prisoner.

When I received a printout of her MY SPACE website, she was more beautiful than I could ever have imagined. It’s a known fact that many radio personalities are not so attractive. That’s why they are in radio. But this DJ, she was a 20-year-old blonde, blue-eyed angel. From reading her profile, we seem to have all the same interests, everything from movies to television shows, to music.

For the past year I’ve found purpose in each mail I send her, sharing my knowledge of how to blossom her talent. Likewise, I’ve become her “man in the box,” a supporter of her ambitions and career, always providing encouragement, pushing her to make the best of each shift, to maximize her potential. She gives me an escape from the misery of the everyday routine, where it’s Groundhog Day everyday.

I’ve asked her to go deep into the station vaults to pull out records that have collected dust. Hits from the ska band The Specials, “Concrete Jungle,” ‘90s hits like the acoustic versions of Stone Temple Pilots’ “Plush” and Foo Fighters’ “Times Like These.” She recently made me cry for the first time when she found a hard-to-find classic, a Smashing Pumpkins cover of Fleetwood Mac’s “Landslide.”

We continue to interact over the radio. The average listener and her boss haven’t any idea that some of her bits and on-air statements are something between her and me.

One has to wonder why such wholesome, sweet women are attracted to bad boys.

Of course, I’ve asked her to write me direct. Meet me. Hasn’t happened…yet. She said she still lives with her parents. Oh my, what would happen if her parents intercepted a letter from a state prisoner!

It’s the possibility of meeting her, turning my fantasy into reality that gives me hope for another day. Three days a week, I get to hang out with her. Four days a week, I’m on my own.

Her latest change to her MY SPACE website says she would meet “anyone.” Also says that one of her favorite movies of all time is “Sleepless in Seattle.” Hmmm…

Meanwhile, as the saga continues, I’ve decided to get back on the Internet myself to list my profile: Virgo, 35 years old, Hispanic, healthy, tan, fit, unemployed and living with another man in a prison cell…Favorite movie: “Sleepless in Seattle.”

The headline to my page will read: Sleepless in Soledad. §

Tito David Valdez Jr. resides at and writes from the minimum security Correctional Facility in Soledad, Calif. Listen to his radio segments on prison life on the nationally syndicated program, “The Adam Carolla Show.” For times, visit www.adamcarolla.com. Tito can be reached by email at davidv@inmate.com, or by mail: Tito David Valdez Jr. J-52660, CTF Central E Wing Cell 126, P.O. Box 689, Soledad, Calif., 93960-0689. Read more of his "Life in the Cage" series here:

Mischief in the prison chapelJailhouse prunoA momentary breath of freedomBreakfast ClubTrappedInstitutialized Evening dayroom Destination ASH

Go to the main page for this month's Rogue Voice

Read more!

Cabby's corner: The mayoral candidate

He’s a rightwing, know-it-all hardliner, a nut, never read a book, wants to bomb the hell out of everybody.

He’s a rightwing, know-it-all hardliner, a nut, never read a book, wants to bomb the hell out of everybody.

‘How are you gonna get elected mayor of San Luis Obispo when all you can talk about is the shit on your shoe?’

CABBY’S CORNER, 1988

The mayoral candidate

A malcontent who wants to make parks safe from dog pilesBy Dell Franklin

Harley keeps his cab as fastidiously clean as he does his own person, and hands out business cards referring to himself as a “Cab Pilot.” Harley is the only cabby on our staff of nine who personally tailors his uniforms. Harley wears one of those little black Greek caps and maintains a neat mustache beneath an overhanging nose and two close-together eyes that have earned him the behind-the-back nickname among cabbies and dispatchers of “Spuds McKenzie.” Harley runs his cab through a car wash at his own expense nearly every day and claims it is as clean as his personal vehicle, a Honda, on whose engine he brags “one could eat.”

Even though my cab is never washed and I drive a filthy, dented, duck-taped jalopy, and I usually need a haircut and present a ragged, threadbare Yellow Cab uniform, Harley and I get along famously. Before becoming a San Luis Obispo Cab Pilot, Harley taught high school in Bakersfield, California.