Trapped

The Downey Police made it known to me off the record that they did not want this club. They disliked the fact that it would bring in minority youth from the neighboring cities like Compton, Lynwood, South Gate.

The Downey Police made it known to me off the record that they did not want this club. They disliked the fact that it would bring in minority youth from the neighboring cities like Compton, Lynwood, South Gate. At 5 p.m., Manuel called again with news that he would be 90 minutes late. Little did I know, FBI vans were parked three houses down, fitting a “wire” on him.

Life in the cage

Snared by an informant and a flimsy wiretap

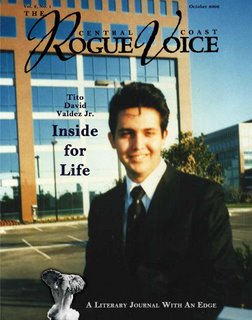

By Tito David Valdez Jr.February 7, 1995

It was a cloudy, gloomy morning in Southern California. My father and I sat together at a courtroom table, side-by-side, inside a criminal courtroom.

Norwalk Superior Court, located on the east side of Los Angeles and dubbed by career criminals as “No-Walk,” was where the district attorney’s office had a 99 percent conviction rate.

Dressed in Los Angeles County jail-issue blues, with our defense attorneys by our side, we faced the final chapter in a courtroom drama that lasted nearly four weeks: A sentencing hearing before an empty courtroom, with no media present, not even court-watchers. Just my mom and younger brother, who sat faithfully through each day of the trial.

The Honorable Dewey L. Falcone, a middle-aged Italian, presided in his full, black robe. Behind him, the American flag, and Lady Liberty holding the scales of justice. Above him, a placard with the words “In God We Trust.” He pronounced sentence.

“I sentence you, Tito David Valdez Jr. and Sr., to 25-years-to-life: On Count I, Conspiracy to Commit Murder; on Count II, Solicitation to Commit Murder. I sentence you both to nine years to run concurrent to Count I. I order you both remanded to the California Department of Corrections, forthwith. This Court is adjourned.”

The prosecutor, Dinko Bozanich, a tall Caucasian in his mid-50s, smiled and shook hands with several Downey Police officers involved in the investigation leading to my arrest. They celebrated their victory, representing the People of the State of California.

I thought of how many peoples’ lives were changed every day in courtrooms like this all across America. The people employed by the courts yield tremendous power. In the hands of corrupt officials, such power seeks convictions over justice, perverts the search for the truth.

The bailiff, a 50s-something, balding Hispanic with beer belly, ordered me to push my father in his wheelchair out of the courtroom so the next case could be called. As I rolled my father out, I looked to the seating area, and observed my mother and brother in tears.

Back in the holding tank—where four Chicanos were beating up a white guy sentenced only to probation—I wondered if our privately retained attorneys would come speak to us to express some kind of apology or condolences. Hours passed by. They never came.

It appeared that our fate was predetermined. The trial was a sham, a mere formality, with actors playing out a script.

Our defense attorneys, Karen Filipi, from the law offices or Robert L. Shapiro, and Richard Leonard, an independent litigator, never visited us to discuss a defense, go over evidences; they never hired an investigation team, or filed motions to obtain discovery or suppress evidence.

Their excuse? Too busy with the O.J. Simpson case.

When I attempted to fire privately retained counsel to obtain new counsel, the judge denied the motion. When I attempted to represent myself, the motion was denied; and when I requested a three-month extension to prepare a defense, denied.

Despite a court-appointed psychologist who provided expert testimony that my father suffered from “organic brain syndrome,” a condition in which physical disorders can cause decreased mental functions, and that he was not competent to assist counsel in a defense, the judge found my dad competent to stand trial. The trial still went forward, with my dad being transported daily from USC Medical Center weighing a mere 95 pounds, wearing full hospital garb and a diaper underneath, with IVs hanging on a rack.

During the 20-minute bus ride back to the L.A. County Jail, I looked out the windows, shedding a tear, absorbing the reality of being sentenced to life imprisonment. I noticed simple sights, which I never took the time to notice before…a mother strolling her newborn to the local market…children buying ice cream and treats from the ice cream truck…a Mexican paisano with a leafblower in his hand….

My mind drifted off to memories of my dad…always available to help me with homework…and my mom…always encouraging me to do my best…my childhood….

***

I was born on August 24, 1970, in Artesia, California. Raised mostly by my grandma, because my mom and dad worked two jobs to make ends meet, I grew up poor. Potatoes and beans with powdered milk for breakfast every day. Same for dinner, but with a twist of Tang. I wore second-hand clothes from the local thrift stores.

By age 7, I moved to an affluent city, Downey, California, which was mostly populated with conservative whites. Some restaurants in the city still posted signs, which stated, “No Niggers Allowed.” It was a rare sight back then to see a black family living in Downey.

My mother, a Mexican national from Guadalajara, Mexico, came to California at the tender age of 16 to work as a maid in San Diego. With Caucasian features, light brown hair, green eyes, light skin, she easily blended in. She quickly learned English and obtained her U.S. citizenship.

My father, born and raised in Espanola, New Mexico, came to California at age 24 after a four-year stint in the U.S. Army. He worked in the booming aerospace industry. In his spare time, he exercised religiously at Jack LaLanne Health Spas and hung out with surfers in Malibu Beach. Eventually, he became an aerospace mechanic at Rockwell International, the company that built the space shuttles, and was located just 100 yards across the street from our home.

Growing up, I saw few Hispanics cast in positive roles on television. Freddie Prinze on “Chico and the Man,” Erik Estrada in “CHiPs.” Hispanics then were stereotyped and cast only as gang members, drug dealers, gardeners, and maids. Not identifying with television personalities, I took an interest in radio, and found inspiration in personality Rick Dees, who hosted mornings at 102.7 KISS FM in Los Angeles.

Using a toilet paper holder as my microphone and my dog “Tiger” as my audience, I practiced being a radio jock. Did my first phone bits by crank-calling people.

As a teen, I enrolled at Downey High School, where singer Karen Carpenter attended. Students were mostly Asian and white, with a few handfuls of Hispanics. Thirty percent of the Hispanics were pachuco swaying Chicanos from the barrios of South Downey who wore Dickies and Pendletons.

Seventy percent were assimilated—looked and acted white—wore Guess clothing and Reebok shoes. We viewed them as lowlifes. They viewed us as gabacho sellouts.

As an assimilated Mexican American, I got the best of both worlds. Attended kegger parties where there was an abundance of hot blonde-haired, blue-eyed chicks, or cruised Whittier Boulevard, scoring on hot Latina women, whose brothers were gangstas.

I noticed that in both scenes, cops were busy breaking up parties. Teens had no legitimate place to hang out. As a result of peer pressure and the desire to be popular and accepted, many, including me, drank alcohol, snorted meth, and ingested LSD.

I saw the tragic consequences of such juvenile behavior. Friends of mine, classmates, overdosed, were killed by teen drunk drivers, or went to prison for crimes committed while under the influence.

At Cal State University, Long Beach, I majored in marketing, and took courses in Chicano studies; I learned the history and struggle of my people, which inspired me: Men such as Cesar Chavez, who fought for farm workers’ rights, and spearheaded the UFW movement; the significance of the Zoot Suit riots; the untimely and mysterious death of prominent L.A. Times journalist and columnist Ruben Salazar, killed in a police action. I left college with great visions committed to making a difference in the world.

***

My childhood dream of becoming a radio disc jockey became reality in 1990. After selling a PC computer to Mucho Morales, a legendary Hispanic radio jock, he arranged an internship for me at K-EARTH 101 FM, an oldies format station. After four months there, I packed my bags and moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, with a demo tape—and a dream—in hand.

I was hired by 97.3 KISS FM, a Top 40 station, doing nights. Did live remotes at nightclubs, car dealerships, and movie premieres. Kicked it with celebrity artists, produced commercials for advertisers.

While there, I pioneered the popular rave culture movement, which was just gaining momentum in Los Angeles. Raves were all-night parties held in abandoned warehouses where drugs like Ecstasy and LSD sold like candy. Except my events were legal, legitimate, held in established venues. I experimented with the concept that teens, if given a choice and outlet, would prefer attending a legit club rather than driving to remote locations, where the potential to get into trouble is higher. The events were indeed successful and attracted media attention.

After a year in New Mexico, I packed my bags again and moved back to Downey, to try the same concept in Los Angeles.

***

It was the summer of 1992, just after the Rodney King riots when I held my first drug/alcohol-free events at different weekly locations, calling the event, “Club Jump.” Hundreds of teens from all over Los Angeles paid $10 apiece to get in, a very steep price in comparison to the $3 cover at the average keg party. The venues I rented could not handle the steady influx of teens. Fire marshals often complained that I was over capacity. Thus, I needed desperately to find a venue that could handle 600-1000 teens a week.

I reached out to the owner of an aging 30,000 square-foot roller skating rink in Downey with the intent of establishing a permanent teen dance club. Naturally, he embraced the proposal, since it made good business sense.

Unfortunately, I immediately faced red tape with the Downey Planning Commission and the Downey police to obtain the necessary permits. First, they complained of insufficient parking. The PTA and school district, supporting my plans, offered to rent me 350 parking spaces in an adjacent lot. Then, city officials complained the rink was not zoned for “dancing,” only for “skating.” After placing this issue on the council agenda because of media attention, the council quickly amended the zoning to include dancing. Despite the resolution, 40 residents showed up to complain about the club, saying it would bring in graffiti, excess traffic, and gangs.

I needed only one last permit, a “teen dance permit” from the Downey Police Department. Shockingly, the Downey Police made it known to me off the record that they did not want this club. They disliked the fact that it would bring in minority youth from the neighboring cities like Compton, Lynwood, and South Gate every week. Despite their blatant dislike for my cause, I submitted my fingerprints for an FBI background check, and paid the fee. The officer who took my prints said, “My advice, take your business elsewhere. You won’t get the permit from us, you can count on that.”

During the lengthy approval process, I continued to successfully promote the weekly rotating dance club. With the handsome revenues, I created a weekly half -hour cable television show, “Hollywood Haze,” which aired on leased access channels on six major cable stations, Mondays at 8 p.m. I obtained sponsorships and sold commercial airtime. The show featured rave culture, celebrity artists, and cast Latino youth in positive roles. Not long after, I landed a job as host of “Full Flavor,” a weekly mix show on 96.7 KWIZ FM, which featured the best deejays spinning house and techno music, airing Monday nights from 10 p.m. to midnight.

With the power of radio and television, I moved from promoting teen clubs in small venues to promoting commercial events in stadiums or arenas, attracting up to 5,000 people. I also promoted 21-and-over nightclubs since such clubs in Hollywood held a capacity of over 1,000 people.

Nevertheless, as a matter of principle, I never gave up the fight, to obtain that last permit from the Downey Police Department.

***

December 2, 1993

A new format of music hit the Los Angeles airwaves. Power 106 FM was the first to play a continuous play list of hip-hop/rap music from artists like Cypress Hill, Dr. Dre, and Snoop Dogg. Gangsta rap, which was once distributed underground, was now commercial.

The rave culture scene was at its peak. Gone were the days of dancing in small clubs. Large-scale commercial events were in. A 1993 New Year’s event, called X-RAVE, put on by the top five promoters in California, attracted more than 20,000 teens to Knott’s Berry Farm in Buena Park, California.

Local law enforcement, the DEA, and FBI were on a mission to squash the rave culture movement because of a few highly publicized cases of teenagers overdosing on Ecstasy or from inhaling nitrus oxide. They were busy shutting down even legal raves to discourage promoters from planning future events. Being highly visible in this rave culture, I became a target of the feds the way leaders of activist organizations in the past, such as the Black Panthers, became targets and victims of COINTELPRO tactics. These illegal techniques included using paid FBI informants to trump up charges or to instigate a target to commit criminal acts.

***

It was a Thursday afternoon when I received a call from a business partner named Manuel Guerra, who had invested in several nightclubs I promoted. He was a buff, dark-skinned, tall Puerto Rican who spoke fluent Spanish. When he spoke English, he had an accent from the barrios.

“Hey Dave, my buddy Carl, the mechanic, he is going to pick me up, eh, in his G-Ride; we will head to your pad at 5 p.m. to chat. He will fix the problem you are having with your car.”

“Okay, cool. Does he have his own tools? Because if it’s the spark plugs that are bad, I may need to provide those.”

“Don’t trip, eh, he has everything. He will know what to do. I’ll see you soon!”

For two weeks, my car wouldn’t start. The local mechanic a few blocks away, changed the battery, the starter, the ignition system, but the problem persisted. With an earth-shaking sound system, which could be heard from blocks away, I figured the new amplifiers in my car were draining the battery.

At 5 p.m., Manuel called again with news that he would be 90 minutes late. Little did I know, FBI vans were parked three houses down, fitting a “wire” on him. They needed extra time to do sound checks. All phone calls he made to me were recorded as well. Manuel would later falsely testify that the dialogue in these phone calls was in “code.” “Mechanic” meant hit man. “Tools” meant gun. “Spark plugs” meant bullets.

Desperate and anxious, I tweaked the ignition wires to get the car to start and drove the car to the local mechanic, before they closed at 6 p.m. Unfortunately, the shop was closing early when I arrived so I obtained a work receipt and left the car at the garage. My father picked me up minutes later and drove me back to the house.

Around 6:45 p.m., my father and brother went to get burgers. At 7 p.m., Manuel arrived in a lowered Camaro IROC-Z with Carl, the mechanic, a tall, buff African American, who looked like a gangsta rap artist, wearing a Raiders jacket. We kicked back and talked about parties, chicks, and cars, while we drank tall-neck Heinekins. My mom was asleep in her room, so I told Carl to keep it down; he was talking loud.

In an effort to obtain a live confession, Manuel brought up my pending date rape case, filed in April 1993, in which a teen girl alleged I raped her at my parents’ house while my brother and father watched television in the room next door. The case was not based on DNA or any forensic evidence, just allegations.

“Hey man, did you fuck her? Come on, you can tell us, we are homies.”

“Nah, man. I didn’t do shit. Downey P.D. is after my ass. They brought up the charges to discredit me, to ruin my reputation. They are mad because the allegations actually fueled my popularity and status. I’ve got five times as many advertisers since I was on the front page of papers, charged with a crime.”

“No shit! You the man. Did she look underage to you?”

“She looked about 17. But she represented herself as 18. You know how it is. Do you ask every chick you meet how old they are? Do you ask them for an I.D.? Even if you did, it could be a fake I.D.”

“You had to do something to her, for her to get the police involved.”

“Here’s what I believe happened. I didn’t give her the job on the cable show. She got pissed, made up a story, and Downey P.D. ran with it.”

“So you think it was a set up?”

“For sure.”

Manuel continued to talk about the situation. I felt a strong buzz coming on as Manuel slipped me a tab of LSD, which fell in my beer. I soon became a little paranoid.

“Why are you asking so many questions, are you a cop?”

“Nah, man, we are looking out for your best interests. We like family,” said Manuel. They both looked at each other as if they got caught with their hands in the cookie jar. Perhaps they thought I made them.

“You know, your trial is in 10 days. Check out Carl, he’s scary looking, isn’t he? He could go up to her and intimidate her into not testifying. The case would go away. He owes me a favor. What do you think?”

“Nah, man. I’ll be the first suspect. Downey P.D. has no love for a Mexican.”

“You’re right, a Latino or black man can’t win at trial when a girl gets up on the stand, cries, and says she was raped. My brotha, you gots a lot to lose. Shee-it. The whole empire you created will fall down if you go to prison. My homies tell me sex offenders got it rough in the pen, if you know what I mean. I’ll do whatever you want—for free. As a favor to Manuel. I’m from the old school, I won’t rat on you,” said Carl, with a confident persuasive tone of voice.

“Okay, let’s look at this situation as if it were a movie. How would you go about it? A carjacking? What about the mom and her together? How would it go down?” I asked.

“Just tell me what to do. If you want her whacked, do you want a head shot, a chest shot?”

“Ah…just whack her, bro.”

“What do you mean by ‘whack?’”

“I don’t like giving specific definitions. That’s up to you to determine.”

Minutes later, my father and brother arrived with burgers but none for the guests, they had no knowledge they were coming over. I introduced them and my brother went to his room to play Nintendo. We ate our burgers while talking to Manuel and Carl. My dad left the room to get another beer.

“Hey Dave, ask your dad if he still has that handgun you told me about. I need it for tomorrow, for security. I got to be packin’ tomorrow at the club. We don’t know who is bangin’ and who isn’t.”

“Hey dad, do you still have that handgun, which you don’t use? We are working a club in Hollywood tomorrow, a shady section.”

“No, I lent it to your uncle Fidel. If you need a handgun, there is a guy across the street who sells them. I’ll be back, bring him over.”

Shortly after, my dad arrived with the neighbor who runs the neighborhood “Homeboy Shopping Club.” He is the Hustle Man of the free world: televisions, radios, VCRs, anything’s on the market, even Uzis.

We inspected a .38 revolver that had six live rounds inside. The price: $200.

“Dad, I need to borrow $100. I have only $100 in cash on me. I’ll pay you back tomorrow.”

“Sure son, here’s $100.” I paid the neighbor for the handgun, and handed it to Manuel. We all laughed as the gun dealer, Felipe, a paisa, talked about how he obtained his merchandise, mostly from local dope fiends who needed quick cash.

Fifteen minutes later, Carl, Manuel, and I jumped in his low-rider IROC-Z, placing the gun in the trunk, and drove to the corner liquor store to buy more beer.

As we turned the corner, FBI agents and Downey Police surrounded the car, pulled all of us out at gunpoint, yelling, “Get down, get down!” We were all handcuffed and placed in separate police cars, transported to the Downey Police Department. Detective Bradfield, the same officer who took my fingerprints for the teen dance permit, the same officer who was lead investigator on the date rape case, was now interrogating me.

He was a tall Caucasian in his mid-60s with white walrus moustache, balding head, and beer belly.

“Mr. Valdez, you were inside a stolen car. Tell me, what was a handgun doing in the trunk? What were you going to do with that handgun, target practice?”

“The handgun was for security purposes. Protection. You should ask Carl, he is the owner of the car.”

“Alright, smart ass, you are free to go. Here’s a phone, call your ride.”

I called my dad. Within 10 minutes, he arrived with my younger brother, entering the lobby. Detective Bradfield arrested my dad. It was a cowardly way to lure him in, as my younger brother, just 15 years old, watched his old man get cuffed and taken away.

“Mr. Valdez, the papa, you are under arrest for conspiracy to commit murder.”

“Huh? What? What do you mean? Who was killed?” asked my dad, surprised, shocked.

Bradfield returned to the interrogation room, after placing my dad in a separate room.

“You sonofabitch, don’t you understand, I paid for this to happen. You fucked with us, now we are fucking with you. I told you to take your business elsewhere. Why did you have to get your dad involved in this? He is now going down with you, you piece of shit.”

My dad and I were booked together into the L.A. County Jail at about midnight. Carl and Manuel were nowhere to be seen. One of them, or both, I reasoned, was a rat who led us into a trap. A case of entrapment. At our arraignment, we made headline news on all the networks.

***

My father and I have served 13 years in separate California prisons. He is currently 69 years old, weighs 180 pounds, and is in good health. I am 36. We write each other letters, our only form of communication. We are both disciplinary free inmates with unblemished work records.

The appeals process has failed us. We are procedurally barred from appeals since 2001 because our former appellate attorney, Richard H. Dangler Jr., filed our briefs 280 days after the one-year deadline mandated by the Antiterrorism Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996. In 2005, after a full-blown investigation by the California State Bar Association, Dangler resigned with charges pending. A 2005 3rd District Court of Appeals opinion, In re White, stated that Dangler ran a “writ mill” for pecuniary gain, employing inexperienced law students and disbarred attorneys to write and file writs that had no chance of success. His staff even forged his name on briefs, filed them late, or not at all.

“Simply stated, the attorney not only took money from these inmates and their families under false pretenses, he gave them false hope that they had some possibility of success—hope that we must now dash because, as even the attorney concedes, the writ petitions are doomed to fail,” the court wrote about Dangler.

At least a thousand prisoners’ appeals have been lost or procedurally barred by Dangler’s gross misconduct. The irony is he ripped off over a million dollars from prisoners’ families. Yet, he won’t do a day of prison time. He won’t pay a penny of restitution since he filed for bankruptcy.

Our claims, which the federal court won’t review, are persuasive and would have changed the outcome of the trial. The prosecutor failed to disclose that his star witness, Manuel Guerra, was a paid FBI informant with a prior criminal record. A tape expert analyzed the wiretap and rendered the tape an edited/altered version with more than 40 splices. In 2002, a juror in the trial came forward with serious allegations of juror misconduct. Under the Freedom of Information Act, the FBI acknowledges in my FBI file under the heading “Accomplishment Report,” that I was under investigation and surveillance in 1993. However, my dad was not.

People who have taken the time to analyze our case recognize the absurdity of the prosecution’s argument. Would anyone have hired a stranger hit man in their own home, a hit man with no weapons of his own, and who would kill someone for free? Should anyone believe a lying paid FBI informant who is a career criminal and has a motive to lie to get paid? If my dad was a co-conspirator with knowledge of an alleged hit to go down, why did he lend me $100 to purchase a handgun when he could have paid the full price of the gun himself? Why did the unintelligble wiretap only capture less than seven minutes of conversation during a 45-minute sting operation when the FBI van was parked just three houses away? If the government can put a man on the moon and get a clear “wire,” what happened in this case?

Supporters such as the Orcutt Republican Club of Santa Maria, Governor Bill Richardson (D-New Mexico), Senator Richard Martinez (D-New Mexico), and other professionals, have already written California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger letters, urging our immediate release via a commutation of sentence, or full pardon. It is a waste of taxpayer money to continue to house my father and me when there was no crime. We don’t even have prior criminal records.

***

The City of Downey has changed. Blacks and Hispanics are the majority. The skating rink was torn down. A new mall was built in its place. Rockwell International, where my dad worked for 33 years, is now a full-blown movie studio—Downey Studios, where Terminator III, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger was filmed. Downey Police still make headlines today for police misconduct against minorities.

Rave parties are now called “Festivals,” take place nationally, and attract 50,000-75,000 teens per event. Law enforcement now sets up stands where teens can test their Ecstasy or LSD to make sure it’s not bunk. As for gangsta rap, what most people thought was a fad, is now a billion dollar industry, still thriving, promoting a lifestyle of pimping, hustling, and drug dealing.

Our application for Executive Clemency has been pending before Gov. Schwarzenegger since March 2005. His office has yet to review our claims of innocence. §

Editor’s note: Readers can view the entire case profile for David at:

www.inmate.com (click on "David Valdez" link), and www.inmatelaw.org.

***

Tito David Valdez Jr. resides at and writes from the minimum security Correctional Facility in Soledad, Calif. Listen to his radio segments on prison life on the nationally syndicated program, “The Adam Carolla Show.” For times, visit www.adamcorolla.com. Tito can be reached by email at davidv@inmate.com, or by mail: Tito David Valdez Jr. J-52660, CTF Central E Wing Cell 126, P.O. Box 689, Soledad, Calif., 93960-0689.

Read more of his "Life in the Cage" series:

Go to the main page for this month's Rogue Voice